This sensor is poised to collect stream data, but the stream has dried up.

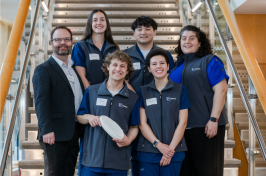

Wil Wollheim (left, conducting research here in a wetter year with former postdoctoral researcher Richard Carey) wants to measure nutrients that flow from beaver ponds.

Wil Wollheim (left, conducting research here in a wetter year with former postdoctoral researcher Richard Carey) wants to measure nutrients that flow from beaver ponds.

Bill McDowell wants to know how humans and climate change will affect the water quality of streams in southeastern New Hampshire. But as those streams become trickles or disappear altogether in the face of this summer’s drought, much of his fieldwork has come up dry.

“The drought is limiting our ability to sample streams — some have dried up completely — and the very low flow makes some experimental work impossible,” says McDowell, Presidential Chair and professor of environmental science.

While most of us in the Northeast are feeling the effects of this hot, dry summer — from the seemingly endless stretch of sunny warmth to the watering bans that shrivel our gardens and crisp our lawns— some researchers at UNH have found the record drought has changed the way they can conduct research.

McDowell’s research group is studying streams that feed into southeastern New Hampshire’s Lamprey River.

“We have sensors in these streams to monitor the chemical and physical parameters and flow has gotten so low in them that we have had to either pull the sensors or just had to do without data for blocks of time,” says Jody Potter, lab manager of the New Hampshire Water Resources Research Center McDowell leads.

Some streams for another project — a collaboration with the conservation group Trout Unlimited to restore trout habitat in streams by adding trees and logs — have also dried up. McDowell’s team has added the wood in anticipation of future flows, but monitoring for changing nutrient dynamics, the bulk of the UNH work, has been put on hold.

Associate professor Wil Wolheim, an aquatic ecosystem ecologist who like McDowell is in the department of natural resources and the environment and studies nearby freshwater, has similarly found some sampling sites dry. For one study, his Water Systems Analysis Group hopes to measure the nutrients and sediments that flow into and out of beaver ponds.

Thirsty Forest

On a small plot of eastern white pines and northern red oaks in UNH’s Thompson Farm Observatory site, the drought’s effects are doubled — on purpose. To learn more about the impact of drought on New England’s forests, associate professor of ecosystem ecology Heidi Asbjornsen and her Ph.D. student Cameron McIntire have built a 900-square-meter canopy of gutters that channel 50 percent of the rainfall away from the trees beneath it.

As New England’s climate changes, “even though we’re expected to have more total rainfall, we’re also expected to have more prolonged periods of drought,” says Asbjornsen.

“The dry weather this summer has certainly amplified the drought we are aiming to simulate,” says McIntire. Initial measurements in this first year of the study have shown that trees are responding to less water by adjusting their stomata, the pores through which moisture leaves a tree, reducing both transpiration — the evaporation of water from the trees’ leaves — and photosynthesis. “I would be willing to bet that this will have a direct effect on tree growth as well, but we don't have that data yet,” McIntire adds.

But this year, those streams are not flowing. “But the beaver pond is still there, so we are monitoring the response of processes in the pond to the drought,” he says. “Hopefully we can compare it with future years that are wetter.”

Other researchers note the value of such comparisons: To a scientist, an unusual year can be a rich source of data, particularly as droughts like this summer’s are predicted to become more common as our climate changes.

“It can actually be beneficial to have a year that is really an outlier when we are doing multi-year studies, so that we can?see results that may differ in a dry versus a typical year,” says Extension professor Becky Sideman, a crop and sustainable agriculture specialist. On the Woodman Horticultural Research Farm at the edge of campus, she’s growing Brussels sprouts and table grapes outdoors as well as tomatoes, peppers and fall-bearing strawberries in high and low tunnels.

The lack of rain has some benefits as well. It’s made scouting future research sites easier, says Wollheim, because the type of surface — sand, mud, rock — on which the stream flows is an important consideration for his work. “We can walk along entire stream channels to see what their substrates are,” he says.

On Woodman Farm, Sideman’s crops have seen far less fungal disease than they do in typical years. “This does, however, have a down side,” she says. “We often hope to see differences between treatments in susceptibility to diseases, and those differences aren’t visible in a dry year like this one.”

?

These projects received funding from the National Science Foundation (McDowell, Wollheim); New Hampshire EPSCoR (McDowell, Wollheim); NH Agricultural Experiment Station (McDowell, Sideman, Asbjornsen, Wollheim); U.S. Geological Survey (McDowell); Town of Durham and UNH Facilities (Wollheim). Sideman’s work was also funded by UNH Cooperative Extension, Northeast SARE, USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, New Hampshire Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, and New Hampshire Vegetable & Berry Growers Association.

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566