INHCC partners Paul and Denise Pouliot near Durham’s Burnham Garrison archaeological dig site.

Readers of UNH Magazine probably know Kchi Niwaskw as New Hampshire’s Cannon Mountain and Stone Face as The Old Man of the Mountain. First recorded in 1805 by road surveyors Francis Whitcomb and Luke Brooks, scientists have dated the structure, which collapsed in 2003, to the retreat of the glaciers about 12,000 years ago. Now just a memory for Granite Staters, it took on symbolic significance after Daniel Webster suggested it was a divine tribute to New Hampshire’s indomitable citizenry and was formalized as the state’s emblem in 1945.

But the story of Nis Kizos and Tarlo claims a far longer pedigree, “somewhere between many hundreds and several thousand years,” according to Paul Pouliot, a member of the Cowasuk band of Pennacook Abenaki People from Alton, New Hampshire. “Nobody knows its exact origin because it’s legend,” he adds. “But once you hear it, tell me you won’t look at Cannon Mountain a little differently.”

And that — looking at New Hampshire from an indigenous point of view — is precisely what a small, patient, determined and resolutely grassroots organization seeks to accomplish. The group is called the Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective (INHCC) and includes Paul and Denise Pouliot, several UNH faculty members and students, local grassroots organizers and community members and several members of other New England tribes. And while the INHCC may have originated in the book-lined offices of three UNH faculty, it’s not about university researchers “studying” indigenous people. In her heavy Russain accent, Svetlana Peshkova, one of those faculty members, lays out the project’s number-one ground rule with unmistakable clarity: “In the collaborative collective, we don’t say we are studying you. We say we are learning with you.”

That M.O. has taken the organization further than even they might have imagined a few short years ago. And, really, they’re just getting started.

The Tale of Two Maps

At UNH, anthropology department chair Megan Howey is one of several faculty members helping the Pouliots and others reframe a predominant local narrative that centers on the indigenous population’s demise.

A map in Howey’s office, dating to 1667 and produced by an English merchant, provides a perfect case in point: It shows dozens of colonial homes, known as “garrisons,” built by settlers with names such as Bickford, Huckins, Wiley and Burnham, and is dotted with churches and mills along the Oyster River and other tributaries leading to Little and Great bays. These were the early English settlements comprising “Durham Plantation” and would eventually become part of New Hampshire’s Seacoast region.

?

The map illustrates the “wild landscape” beyond the settled areas in simply sketched mountain tops and small illustrations of wild animals such as deer, bear and wolves. But something, or somebody, is missing, and that would be the people who had inhabited the place for millennia, and whose language is inscribed on modern-day rivers, mountains and cities.

“Almost from the beginning, the indigenous people of New Hampshire have been fighting a narrative of demise imposed on them by Europeans,” says Howey, who holds the Hayes Chair to study the culture and history of New Hampshire. “But in order to change the narrative, you have to create an archive of knowledge.”

One of those working on just such an archive is Peshkova, Howey’s colleague in the anthropology department. With guidance from Peshkova, the INHCC maintains a blog site that serves as home base for a number of interesting initiatives supporting its educational mission, including a new kind of state map that balances indigenous and non-indigenous versions of key places and events. “The Indigenous New Hampshire Story Map is a digital work in progress, so it can be added to over time as new historical information emerges,” says Peshkova.

An alternative history of New Hampshire — N’dakinna — is already emerging in the map’s some 30 annotated points, which touch on everything from legends like Stone Face/The Old Man of the Mountain to the recasting of historical events, including the infamous Oyster River Massacre of 1694.

You can see the official history of the well-chronicled attack from your car on Route 108, one of the historical highway markers intended to convey the state’s past. It reads:

On July 18, 1694, a force of about 250 Indians under command of the French soldier, de Villieu, attacked settlements in this area on both sides of the Oyster River, killing or capturing approximately 100 settlers, destroying five garrison houses and numerous dwellings. It was the most devastating French and Indian raid in New Hampshire during King William’s War.

This account isn’t necessarily incorrect, but according to the INHCC Story Map, it exemplifies a nai?ve history pitting the “savage Indian” against the “innocent settler” and glosses over the skill with which the French often manipulated native people to fight their battles against the English — who also behaved badly and were not universally loved by native peoples. To that end, the Story Map notes that “the massacre was carried out with French firepower in the hands of the Abenaki people.”

?

In her office, Peshkova elaborates on the difference. “History is more complex than we record or imagine it to be,” she says. “No attack happened unprovoked, and if it did happen, there were other stakeholders involved in violence that the marker does not mention.”

The collaborative collective also counts several UNH students among its longstanding members. Caitlin Burnett ’20, an anthropology and sustainability dual major from Conway, Massachusetts, has worked with Peshkova since her first semester at UNH. She was part of the successful effort to get Indigenous Peoples’ Day recognized by the UNH faculty senate earlier this year and produces a podcast for the INHCC exploring various topics in indigenous culture.

Burnett says participating in the INHCC has changed the way she thinks about her education. “I love the collaborative,” she says. “We get out of the college bubble and into the community. Also, we’re all partners. Students are usually at the bottom rung of the ladder, but the collaborative collective is a very flat organization. It’s made me feel more confident and yet humbled by the people I’ve met.”

Unearthing New Narratives

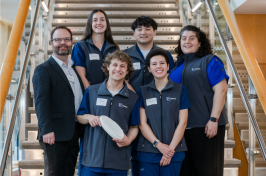

Near the shore of Oyster River, Howey is directing an archaeological dig that’s uncovering not only stone foundations and artifacts dating to the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries but also fresh glimpses into the impact of European settlement on the people and place. Today, she and half a dozen “citizen scientists,” as well as her students, sit in a circle outlining the Burnham Garrison, each with her or his own bucket, small shovel and other tools of the trade.

?

Count the Burnhams among the period’s luckiest — or perhaps shrewdest — of their Durham Point neighbors. First, at 288 square feet, their dwelling was among the more capacious of the neighborhood and housed as many as seven family members in the late 1600s. Even more fortuitous, at least for the Burnhams, they alone among nearby settlers were spared during the height of hostilities in 1694.

A brightly colored shard of pottery unearthed by Emily Mierswa ’17 underscores the former point: Howey suspects it’s a fragment of Westerwald, a German brand that only well-to-do families could afford. A few weeks later, Ryan Rybka, a UMass doctoral student working with Howey, discovers a smooth, black stone tool that sheds some light on the latter point. Howey identifies the object as an indigenous implement — “most likely an axe, which might have hung above the Burnhams’ hearth,” she explains.

The axe find excites her because it supplies yet another piece to the puzzle about the early years of European and Native American relations. “The presence of stone tools found in the hearth of an English family house gives us a clue that settlers and natives weren’t always at each other’s throats,” says Howey. “The settlers, in particular, depended on indigenous peoples.”

She runs this thought past Paul Pouliot, who works at Howey’s sites in search of his own past. He nods his agreement. On the same day, Pouliot is examining a boulder overhang near the Burnham site.

Howey first met the Pouliots in 2010 during the repatriation of indigenous human remains that had been removed when the Seabrook power plant was being built. Retiring after working 32 years as a mechanical engineer, Paul had begun pouring his seemingly bound- less wellspring of energy into learning more and educating others about his tribal history.

Pouliot’s interest in precolonial history dovetailed perfectly with Howey’s professional interests in the recent Anthropocene, the hotly debated epoch when humans began to shape the physical world as much as natural forces did. When Howey successfully applied for the Hayes Chair, she included Paul and Denise Pouliot as co-researchers, and they also became founding members of the INHCC.

“I’m touching this stone and wondering how it would have been used by my ancestors,” Pouliot says. “Maybe they would have sought temporary shelter here during a hunt or a move.” His fingers trace a pair of tiny chips and a nearly imperceptible curlicue pattern on one of the stone’s flat surfaces that he suspects were made by native hands. “Site areas like the Burnham Garrison are tribal as well as colonial.”

A Dance of Defiance

The image of Pouliot running his hands over the giant boulder and looking for traces of his history has its literary parallel in another project, this one called “Dawnland Voices.” Published as a book in 2014 by UNH English professor and INHCC member Siobhan Senier, it continues to thrive as an online publication. Together with tribal authors and editors from around New England as well as colleagues at UMaine, UMass and Bryant College, Senier publishes a wide range of original writing.

“One of the magical parts of producing Dawnland Voices is the power of memory uniting the people living today with those who came before them,” says Senier, whose students provide back-end support for the project’s website and manage the Facebook group used to call for submissions.

?

To read selections from Dawnland is often to witness intensely personal dialogues with the past, rooted in a struggle to forge an identity in the present. In place of picks and trowels, the authors use words and images — and even dance — to break through the rocky soil of modern life. Take, for example, the nonfiction writing of Tim Blanchette, an indigenous rapper who calls himself Mohiks Eagle’s Fire — Mohiks for short. Mohiks writes with searing honesty of a life that seems to hang precariously in the balance. Having survived mental illness, alcoholism, the loss of family members, imprisonment and attempted suicide, he has found purpose through competitive traditional dance, which he describes as an act of self-preservation.

“Dancing as our ancestors did, each of us adding ourselves to the dance,” keeps the culture alive, says Mohiks. But the dance, although joyous, is also rooted in bitter struggle, as Mohiks attests:

We dance in defiance of those who made our way of life illegal. In defiance of corporate mainstream society that steals our culture and identity, misappropriates it, and then sells it to the masses. In defiance of mainstream society that turns our ancestors into Disney characters and sports team mascots. As long as we continue to dance, we are free.

EXPLORE FURTHER

INDIGENOUS NEW HAMPSHIRE

indigenousnh.com

This is the place to start, with links to the INHCC Story Map, podcasts and other material that has been curated by UNH faculty and students and tribal collaborators.

DAWNLAND VOICES

dawnlandvoices.org

Seven issues of the publication are available and include poetry, personal narrative, photography and other examples of indigenous writing. A wide range of styles and experiences.

COWASUCK BAND OF THE

PENNACOOK ABENAKI PEOPLE

cowasuck.org

History and events sponsored by the New Hampshire indigenous group led by Paul Pouliot.

MOHIKS EAGLE FIRE

mohiks.com/home

The official website of Mohiks, where you can listen to one of his recordings and watch him perform a dance.

“Since settlers arrived, they began telling the story about the dying indigenous cultures,” Senier explains. “The voices in Dawnland are striving to break out of the imposed narrative of demise.

“Many of us think of Native Americans as living on reservations or know them mostly from watching them at powwows, but the truth is they mostly live off the ‘rez,’” she notes. “They gather at kitchen tables, popular diners, tribal offices or museums or, in the case of Mohiks and his followers, on YouTube.”

The Way Forward

One of the INHCC’s projects involves establishing a Native American and indigenous studies minor at UNH. The minor would furnish a key milestone for recruiting greater numbers of native students and faculty to campus and educating all UNH students about indigenous heritage, locally and globally. Besides, Peshkova points out, “As a land-grant university located on what were once indigenous lands, UNH has to include indigenous studies, doesn’t it?”

And what of the future of the INHCC? Its members are unanimous in wanting it to keep functioning as a grassroots, informal but disciplined project unbound by any single institutional governance. “The collective’s work will always reflect its three foundational goals: local focus, activism aimed at restorative justice and public education writ large,” says Peshkova.

Howey offers yet another perspective: “In addition to making indigenous resources broadly accessible, we want to offer as an example to others a model partner- ship built on trust and understanding that endures even when there is strong disagreement,” she says. Howey recalls a mentor who counseled her that researchers must learn to “sit with discomfort” — an expression Howey regularly repeats to herself. “It basically means knowing that we may not always be able to fully reconcile scientific and spiritual connections to artifacts. But we can always remember to respect each other.” ?

-

Written By:

Dave Moore | UNH Cooperative Extension