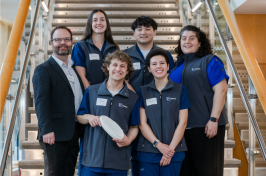

Allison Friend-Gray, Sarah Terry and Kayla Reeves?work on a team exercise during?the Inquiry Teaching Methods course taught by UNH Cooperative Extension. ?

Before young children set foot in a classroom, much of what they learn is the result of their own curiosity and unstructured exploration. During their toddler years, many learn the word “why” — and discover its ability to both amplify their understanding of the world around them and drive adults crazy. Once children enter grade school, however, their naturally inquisitive natures are often circumscribed by a curriculum rooted in systematic lesson-learning and fact memorization.

With the help of UNH Cooperative Extension, teachers in New Hampshire are learning an alternative teaching method that aims to bring excitement and wide-eyed wonder — and a more successful approach to learning — to the classroom.

Inquiry-based learning is a student-driven method that encourages exploration of the world through questioning, observing, investigating, testing and discussing results. Using a curriculum developed by Exploratorium’s Institute for Inquiry, youth and family field specialists Sarah Grosvenor and Claes Thelemarck, and Lara Gengarelly, Extension associate professor and specialist for science education and outreach, are teaching an ongoing series of courses on inquiry for K-12 educators.

This past June, the team held “Inquiry Teaching Methods: Grounding STEM Education Programs in Science Practices” at the Children’s Museum of New Hampshire?in Dover. Over seven weeks, 17 teachers learned the fundamentals of inquiry-based instruction and how to implement Next Generation Science Standards practices into their existing curriculums, including how to ask investigable questions, plan an investigation?and communicate results. As a part of the course, the teachers taught a lesson in their classrooms that incorporated inquiry components and specific science practices, during which Grosvenor, Thelemarck and Gengarelly provided classroom observation and support. They spent the last class sharing and discussing their experiences.?

“I like that the inquiry method allows students to ask and answer their own questions,” says Allison Friend-Gray, who teaches fifth grade science at Dover Middle School in Dover. “It helps raise student engagement and interest in science. After the first time we did an inquiry, one of my students raised her hand to spontaneously announced that she ‘loved doing science this way.’”

“When my students were able to dig in to what they were doing, they came up with deeper level questions then I could have even imagined [and] they were confident and had fun,” says Griffin. “It wasn't just a boring experience where they followed a sheet of paper that told them everything they needed to do.”

For Friend-Gray’s classroom inquiry project, she asked students to observe and formulate questions about pond snails and fish. She reported that getting away from an overly scripted teaching approach elicited a great response from her students, whose questions included, “Do fish get lonely?” and “Why do snails use shells as their homes?”

First-year teacher Heather Griffin, who teaches second grade at Chamberlain Street School in Rochester, decided to use a somewhat unique inquiry-starter to grab her students’ interest. She set a large jar with a few raisins floating in Mountain Dew on her desk. It’s pond water and pond lice, she explained. Then, Griffin drank the “water” and ate the “lice.” The rouse worked its magic: Her students were repulsed, but hooked. From there, they went on to explore why some objects sink and some float, make various predictions and test theories.

“The changes I noticed in my students were pretty significant ones,” says Griffin. “Like many teachers, I have very different ability levels in my classroom. I have students who can't read and students who are reading at a fourth grade level. Giving them very little direction and having them come up with their own questions and experiments made a world of difference.”

The success of the inquiry method isn’t confined to grade school. Jennifer Larrabee, a preschool teacher at Storybook Hollow Early Learning Program, found the approach fired-up her class of 3?year olds.

“[The inquiry method] made me realize how much more I could get from them and how much deeper I could push our learning and investigations,” she says. “It helped me to dig a little deeper and give a little less information and instead let them figure it out — because they can!”

Due to demand, Grosvenor, Thelemarck and Gengarelly are planning more multi-class inquiry method courses for educators that align with national recommendations for professional learning. One of the most valuable features of the courses, notes Gengarelly, is the opportunity teachers are given to practice what they?learn?with the support of their peers and the Extension team.

“Given that we work with them for seven sessions — approximately 25 hours total — we really start to see a transformation in the teachers’ instructional approach mid-way through the course,” observes Gengarelly. “These kind of results are typically difficult to achieve in a one-day workshop.”

Giving participants the opportunity to apply what they’ve learned in their own classrooms, then share and discuss the impacts on their students, has been key to the overall success of the course — and a feature the Extension team added to the Institute for Inquiry’s curriculum.

“That’s when teachers have their ‘ah-ha’ moments,” Grosvenor explains.

“When my students were able to dig in to what they were doing, they came up with deeper level questions then I could have even imagined [and] they were confident and had fun,” says Griffin. “It wasn't just a boring experience where they followed a sheet of paper that told them everything they needed to do.”

And that’s a win for students and teachers alike.

-

Written By:

Sarah Schaier | College of Life Sciences and Agriculture